Open access: addressing your concerns

Open access (OA) is the practice of allowing academic outputs to be available to all, free of charge. Generally this applies to journal articles, but some effort is being made to apply OA to monographs and other outputs.

Open access (OA) is the practice of allowing academic outputs to be available to all, free of charge. Generally this applies to journal articles, but some effort is being made to apply OA to monographs and other outputs.

Although OA can be traced back to the 1940s, the modern movement began in the 1990s, and emerged first in the sciences. The earliest free online archive was arXiv, established in 1991. PubMed, an online repository for medical research, was created in 1997, and the ePrints software was developed in 2000.

The movement gained momentum in the early 21st Century, and has now become mainstream, with many funders mandating its use for publications arising out of the research they’ve funded.

UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), which brings together the UK’s research councils, launched their new OA policy in April 2022. This followed policy changes by Wellcome and the National Institute for Health Research. These new policies are under an international initiative called Plan S, and the next OA requirements for the REF are likely to follow suit.

With this significant step, the Eastern Arc OA and Scholarly Communications Group has prepared a series answers to common OA concerns that academics and researchers across the Arc may have.

Please follow institution-specific advice at UEA, Essex or Kent for detailed step by step guidance about meeting specific funder requirements at your home university.

-

Fully open access journals are often newer than journals based on a subscription model, and so have not had as long to establish a reputation. However, this shouldn’t be a barrier to publishing in them:

- Most academics now recognise that open access is a well-established, growing, credible and fundamental part of the research publishing landscape.

- Many funders, including UKRI and the Wellcome Trust, now require publication in fully open access journals, as laid out by Plan S. Plan S is a set of open access principles that has a growing number of international signatories.

- There is increasing emphasis by many institutions on recognising the intrinsic value of an article or other output, and not the publication where it appeared. Campaigns like the Declaration on Research Assessment (or DORA) are helping to reinforce this position, and the Research Excellence Framework (REF) explicitly states that publication venue should not be a factor in assessing a research article.

- Publishing in a traditional subscription-based journal is not a guarantee of quality, and there are examples of bad practice in many journals.

- Open access publications sometimes make use of open peer review, which further enables the quality of the work to be demonstrated.

Here are some tools for identifying good quality open access publishers.

-

Funders are trying to make sure that public money is used for the public good, to ensure that research is available to read and re-use, to reduce the amount of money paid to publishers and to prevent duplication of research and effort. This is why they have created the current open access requirements.

While these may seem complicated and restrictive, there are nearly always exceptions that can be used if you have a specific publisher in mind. You are free to publish where you wish; however, some journals make it easier than others to comply with the requirements.

Similarly, your funder or institution may only be prepared to pay for your open access fee or article-processing charge (APC) if you publish in certain journals.

More broadly, there is an argument to be made that the expectation that you only publish in a small number of highly-ranked journals is actually a larger impediment to academic freedom.

-

Although it is true that fake open access journals exist and exploit the ‘publish or perish’ expectation in academia, it is certainly not the case that all open access journals are predatory.

Fake journals are always open access, as they take advantage of the ‘pay to publish’ business model to lure researchers into publishing their articles.

So, how can you tell the difference? Here are some ways to spot the predators.

- Aims and Scope: A predatory journal often has a very wide scope and may use names like ‘International Journal of…’ or similar title that sounds very generic. Remember, most journals have a very specific scope.

- Invitation emails to submit: Though it can be common for journals to send out ‘call for papers’ emails, it is not common for the promise of publication to be certain. It is also rare for journals to send emails directly to researchers asking for manuscripts. If you get any of these emails, just delete them.

- Grammar and spelling: Predatory journals will often have strange or incorrect grammar and spelling. This can be on their website or in correspondence. If a journal promising ‘to join hands with you’, or praising you as ‘a well esteemed researcher’, it is probably a scam.

- Submission and retraction fees: The submission fee for a journal should be visible and communicated in a call for papers. Surprise fees are common amongst predatory publishers, and so are retraction fees. If you are asked for a retraction fee, contact your library team for support. If you have submitted a manuscript to a journal and realised too late that it is predatory, they might try to get you to pay to have the article retracted. Otherwise, they could publish the paper, which means you cannot publish it anywhere else.

- Timeline: A journal that offers a very quick timeline from submission to publication is extremely suspicious. Remember, there should be enough time to complete the whole peer review process, so if a journal promises to publish your paper in two weeks, it’s probably because they are skipping the peer review process completely.

The ‘Think. Check. Submit’ tool provides a useful checklist for you to use when assessing a journal. Remember that you can also always ask your library team for support if you are unsure, or just want a second pair of eyes to check your assessment.

-

Open access may actually be required for career progression!

- Firstly, open access is increasingly being included as a requirement in job specifications.

- Secondly, making your work publicly available allows more people to access it, and therefore it can enhance your profile and reputation.

- Finally, many important funders require open access as a condition of their funding. As a researcher’s funding record is often an important factor in career progression, open access is a fundamental part of this.

-

Copyright does not protect ideas, only their expression. If you told someone your research idea in a café and they went ahead and developed the idea before you were able to, you would have no protection.

The best way to protect your ideas is to write them down, register them and share them openly. This is how Turnitin works: it compares text in a document with text on the internet and if it finds anything similar it flags it up.

In the same way putting your research onto an open access platform means everyone will see that it is your idea and if anyone tries to steal it, it will be easy to spot. Use OSF, Aspredicted or Octopus platforms or ask your colleagues which ones they use.

If there is any part of your research that you want to keep to yourself, especially if it is commercially valuable or sensitive, you can still do this, use FAIR Principles to ensure your work is “as open as possible and as protected as necessary.”

-

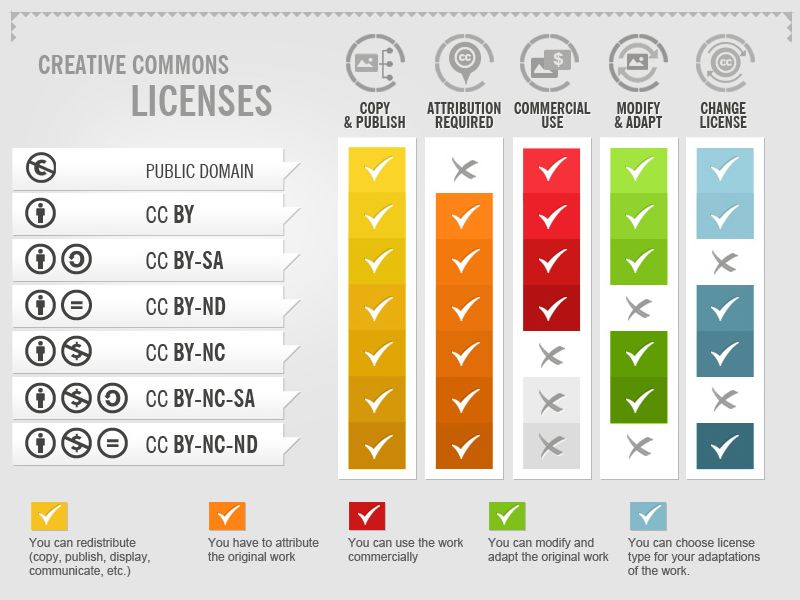

Creative Commons (CC) licences vary in the levels of protection they offer. Different licences enable the author (or copyright holder) to make it clear how users can and cannot reuse the work.

By considering which CC licence works best for you, you are helping to ensure that your work is only used in the way you choose, ultimately providing the level of protection you feel is necessary.

-

Current copyright law that assumes that all content protected by copyright is, by default, ‘all rights reserved’; in other words, you need permission from the creator before you can copy, adapt, or share the work.

When you publish in a subscription journal it is common to be asked to sign an agreement transferring copyright to the publisher on publication. This doesn’t happen when publishing open access and you or your institution retains the copyright.

For open access publication most publishers use a set of standard licences known as Creative Commons that allow authors to make their content free to share and re-use. Attaching a Creative Commons licence to a piece of work lets people know immediately that they can freely share and re-use the content.

These licences can seem confusing at first, but they are relatively simple when you understand the acronyms and the level of protection they provide for your work.

- ‘BY’ Attribution (meaning appropriate credit) is always required.

- ‘NC’ (non-commercial) indicates that commercial uses are not permitted.

- ‘ND’ (no derivatives) indicates that adaptations are not allowed.

- ‘SA’ (share alike) – indicates that adaptations of the original work must be licensed under the same terms (so additional restrictions cannot be imposed by people creating derivative works).

These permissions, and the different ways they are combined, are made clear in this graphic.

-

Publishing open access is actually a good way to ensure you can keep certain rights over your work. When publishing open access, you can control the rights people have to use and re-use your work by assigning a Creative Commons (CC) licence, as we outlined in the section above.

Different CC licences allow for different levels of reuse, meaning you decide which rights to retain. Do be aware that if your research is funded, either by your institution or an external funding body, they may recommend or require that you use a particular licence on your publishing research.

In contrast, publishing via the traditional route (i.e. behind a paywall) often means you sign over the copyright to your work to the publisher. In doing so, you give the publisher the rights to your work, meaning your own reuse may be limited in the future.

If you are concerned about giving away the rights to your work when publishing in a subscription journal, you can use the Rights Retention statement on submission to the journal, and place a prior licence on a certain version of the work.

More information about the Rights Retention Strategy is available on the cOAlition S website (but please note that any research can make use of the statement, whether it is cOAlition S-funded or not).

-

There are ways to work through this provided you address it at an early stage. For each item consider whether:

- the copyright has expired

- there is a clear statement that that the work can be used under a Creative Commons licence

- use of the material falls within the description of ‘fair dealing’ under UK law

If none of these apply and you decide that you need to get the permission of the rights holders to include their content, make your plans for open access publication clear.

Copyrighted material can still be protected on an item-by-item basis within an OA book or article.

-

University repositories and reputable open access platforms are managed according to international standards. Copies of works available from them are held alongside rigorous metadata clearly describing their provenance and the version uploaded. Where the version of record is not held, the Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) or a Preprint may be available and, where possible, there will be links to the publisher’s version of record.

The AAM is the version of the work after peer review has taken place and changes have been made, but before any publisher type setting, branding or copyediting is in place. If a publisher platform has been used to create the AAM there may be some branding present but no page numbers, volume or issue information. The content, however, will be just the same as the Version of Record or the publisher’s version. This is the version most usually held in university repositories.

A preprint is an early version of the same work. It will not have been peer reviewed, but it will contain valuable information and insights. These versions are found on preprint servers like ArXiv, and for many disciplines they form a valid part of the scholarly record and can be cited as works in their own right.

As open access is required by more funders and government bodies, copies of the version of record for an increasing number of works are available from university and subject repositories. These versions are identical to the publisher’s version and can be used and cited in the same way.

You can find any of these versions on Google Scholar and bibliographical databases, and each will be clearly labelled. You need to cite the version you are using but otherwise there is no difference in the validity of the work, whether you got it from a repository, the publisher’s web site, or a printed journal.

-

At the start of any research project, you should develop a plan as to how you are going to publish your ideas.

This will include how and when you will make your work available, and it will include any restrictions on that. If you think that any part of your research will have commercial potential, then you need to consult your university innovation and enterprise team before you decide what you can share and what you can publish.

They will help you decide what can be developed into a business idea and what part of your work can be made available in advance. Making some aspects available before you have developed the commercial possibilities may even help you attracting investment, collaborators, or customers.

Whether you are making this part of your research available open access or published behind a publisher’s paywall, this decision needs to be made as you will not be able to publish anything affecting you patent until it is granted. In fact, making your other work open access early on will improve the reach and potential of your research to support your patented product.

-

Most funders, universities and other supporters of open data and open research support the principles of FAIR data.

These principles state that research data should be findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable (or FAIR). This is so that research process is as transparent, reproducible and as credible as possible.

The reusable aspect also requires that all due care has been taken to ensure that the interests of all participants are protected through GDPR and ethical processes.

The FAIR attitude is that data, and research in general, should be “as open as possible and as restricted as necessary.” This means that instead of dismissing the idea of any data sharing at all, you should take the time to assess your data and work out how it can be made safe to share, through processes such as minimisation and anonymisation, or by separating sensitive data from non-sensitive data like interview and questionnaire tools and methodologies.

- Minimisation of data means that you do not collect more data than you need (e.g. do you need the precise dates of birth, or will a range suffice?)

- Anonymisation involves removing any identifiable detail at an early stage in the processing – e.g. during the transcription of interviews. You can also make sure you have discussed how you will be using, sharing, and disseminating your work with your participants at an early stage. help them understand how you will be protecting their identities while ensuring the widest impact for their contribution.

Funders and publishers will expect you to be able share the data that supports your results in a safe way, and this can be documented at the start of your work in your research data management plan. Your university will be able to support you in this.